In last week’s post, we introduced the concept of grit. Before we get into the details of today’s article, it’s worth revisiting girt’s definition. Here's a recap:

“Grit is defined as perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Grit entails working strenuously toward challenges, maintaining effort and interest over years despite failure, adversity, and plateaus in progress. The gritty individual approaches achievement as a marathon; his or her advantage is stamina. Whereas disappointment or boredom signals to others that it is time to change trajectory and cut losses, the gritty individual stays the course.”

We also took a closer look at grit’s correlation to elite sport. What did we find? For one, according to recent evidence, elite athletes across many sports are grittier than their non-elite counterparts. Secondly, those same athletes more consistently commit to their sport over the long haul - in other words, they stick to it. And lastly, the grittier athletes (the elite), were more adept at persevering through challenges compared to non-gritty athletes.

But the question we should ask ourselves - the same question researchers in this field are asking themselves - can grit be developed? Or do we simply have it or not? There’s not a lot of scientific evidence that can help answer these questions...yet! But according to Angela Duckworth - behavioural psychologist at U Penn who’s leading the charge on grit research - there are ways students, athletes (and anyone for that matter) can develop this quality. In this post, we’ll take a look at some of the most recent - and hopeful - evidence on how to build grit along with anecdotal insights from elite environments across other sports.

How Can We Build Grit?

It Starts with Your ‘Mindset!’

For those of you who’ve read Carol Dweck’s book - Mindset: The New Psychology of Success - you’re familiar with the concept of fixed vs. growth mindsets. For those that haven’t read the book (or the research on the subject), let me provide a quick synopsis. An individual with a growth mindset believes that their abilities can be developed and acquired through both effort and experience. When encountered with setbacks, growth minded individuals acknowledge their shortcomings and aspire to improve upon them - rather than presuming it’s due to some innate quality. A fixed minded individual, on the other hand, views their abilities as innate, something they’re born with. They're either good at certain things OR not good.

Examples of these mindsets as they relate to tennis could be as follows. After losing a tight first set of a match, Player A gets down on him/herself and essentially throws the second set away. Afterwards, they claim that they ‘always’ lose matches when they don’t win the first set. This would be a fixed mindset approach - nothing will change the fact that if they lose a close first set, the match is gone. Based on Dweck, it’s this type of mindset that may lead to negative or counterproductive actions, which in turn lead to a loss of focus, a decline in competitiveness, and so on, in the second set.

Let’s use the same example to illustrate the contrasting ‘mindset’. Player B believes that losing a tight first set doesn’t mean they’ll lose the match. In fact, from their standpoint, it’s a learning opportunity - what worked, what didn’t and how can I adjust to have a chance at winning the second set? While this example may seem obvious, how many times have we seen players ‘go away’ after a tight first set (insert any type of resembling scenario here). They either have a good backhand or they don’t, they’re either bad in the wind or not. They either can’t play on fast surfaces or they can. Unfortunately, these types of mentalities - or mindsets - riddle the tennis world.

So when it comes to grit, why is mindset important? Duckworth and Dweck collaborated to answer this question. They questioned over 2000 high school students - what they found was that those who had a growth mindset also had more grit. Further to that, those who were grittier earned higher grades and were more likely to persist through college.

So How Can We Develop a Growth Mindset?

According to research (Bashant 2014) on the subject, the type of feedback teachers and coaches provide their players may have an impactful role on their mindset over time. For instance, if a coach is praising a player’s forehand, this will undoubtedly feel good for the player in the moment - I mean who doesn’t enjoy praise? But what the evidence is telling us is that this feeling may be momentary. In fact, it could contribute to a fixed mindset approach on their forehand in the future. For instance, what if their forehand is off on a particular day? The thought process might go something like this: “I thought my forehand was good, coach said it was, but maybe it isn’t?”. On the other hand, if a coach praises a player’s forehand in terms of their behaviour, actions or attitude towards its improvement (instead of merely saying the forehand is good or bad) - i.e. their ability to focus on a particular technical cue, or the fact that, in this moment, they’re being aggressive with the forehand - this will foster, according to Dweck, a growth-mindset.

What else can we learn from the theory of mindset? Remember in last week’s post, we highlighted the importance of effort when it comes to grit. It seems that Dweck is also a big proponent of effort - that through continuous hard work, a growth mindset can be achieved. However, that’s not the ONLY factor... and Dweck admits it. In a 2015 article, Dweck had this to say:

“Perhaps the most common misconception is simply equating the growth mindset with effort. Certainly, effort is key for students’ achievement, but it’s not the only thing. Students need to try new strategies and seek input from others when they’re stuck. They need this repertoire of approaches—not just sheer effort—to learn and improve.”

The same goes for tennis and sport. Effort alone, as we’ve all seen before, isn’t enough - both in the training room and the competitive arena. But before we explore alternatives to effort when building a growth mindset, I’d like to highlight a few minor points that, according to Dweck (2015), should first be understood:

We’re all a mixture of fixed and growth mindsets

We probably always will be

If we want to move closer to a growth mindset in our thoughts and practices, we need to stay in touch with our fixed mindset thoughts.

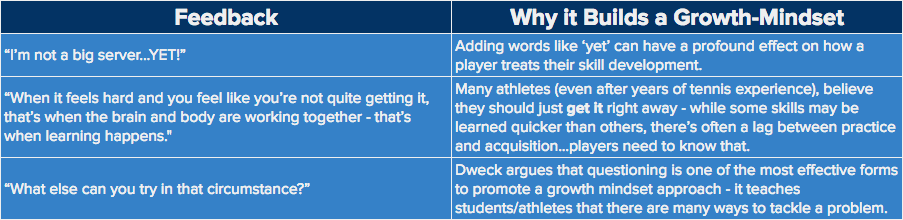

Her point is that you’re not one or the other - but understanding the difference between the two and then being aware when a fixed mindset thought, phrase or action manifests itself, is an important part of the process towards growth - and it always will be. Here are a few suggestions that coaches can use with their players (and athletes), to foster a growth mindset approach (adapted from Dweck 2015):

Deliberate Practice

Here’s another way to improve grit - engage in deliberate practice (DP). I won’t get into the ways in which this can be done and why it’s beneficial (as I’ve written an entire post on this subject). What we’ll do instead is look at the relationship between grit and DP, and how they feed off each other.

Similar to mindset, when Duckworth explored deliberate practice and it’s relationship to grit, the results spoke loud and clear. In a 2016 study, conducted alongside Ericsson - the founding pioneer on DP - participants from the National Spelling Bee were administered a series of questionnaires to determine their study habits along with their grit scores. According to the results, grittier students spent more time in deliberate practice AND ended up performing better (making it into deeper rounds) of the spelling bee. The authors concluded that deliberate practice (solitary studying) predicted spelling bee success better than any other form of practice (re-reading and quizzing).

How Does Deliberate Practice Develop Grittiness?

Recall that deliberate practice isn’t exactly enjoyable. However, when Duckworth looked through her spelling bee data set again, she noticed that, out of the performers that did the best, those that were grittier found deliberate practice to be more enjoyable and more effortful. What we can perhaps infer from this is that, over time, performers begin to see the rewards of their deliberate practice, which makes them want to do more of it, which in turn, makes them grittier. And being grittier, in turn, pushes them towards more deliberate type of practice. It’s a circle that continues to feed off of itself.

One more point, as it relates to tennis/sport. We know that DP is challenging - it requires full out concentration, varied practice strategies and delayed gratification (i.e. the benefits of the practice aren’t immediate). From personal experience, this again is what holds many players back - they want improvements NOW. One thing I know about the adaptation process - other than that it’s complex and not fully understood - is that progress occurs AFTER recovery from practice/training. That’s true for skill practice just as much as for gym training. The brain needs time to process all of the new information, create new mental maps and then and only then does the result of that intense training kick in. Players and coaches need to understand this delicate interplay.

Training Environment

While there isn’t much data to support this (in terms of it’s association with grittiness), it’s safe to say that being in the right environment, impacts the way an individual behaves, thinks and ultimately, shapes their values. Here’s a story that Duckworth shared about building a gritty culture. She was invited to the Seattle Seahawks (pro NFL team) facility to meet with head coach Pete Carroll, and his staff. After many conversations and observations with Pete and the organization, she found that the entire team, from the training staff, front office to the players - all had made a commitment to be a Seahawk. What does being a Seahawk mean? According to Carroll, when you’re a Seahawk “You’re a competitor, you have what it takes to succeed, you don’t let setbacks hold you back. Grit is who you are”. Yes Carroll is familiar with Duckworth’s research and uses grit to help him build the Seahawks culture. When you’re part of the organization, no matter who you are, you do things in a certain way. The Seahawk way.

There’s a couple things that you can do, according to Duckworth:

“If you want to be grittier, find a gritty culture and join it! If you’re a leader, and you want the people in your organization to be grittier, create a gritty culture”.

You can follow in the footsteps of Carroll and build grit into your training environment (via various ways that have been discussed). For coaches, this seems like the most likely scenario.

Dan Chambliss - a sociologist who’s studied Olympic swimmers for decades - echoes the words of Duckworth; “the real way to become a great swimmer is to join a great team.”. The same can be said about tennis players. If you want to become better, find the environment that will challenge you to improve and grow. Pick the NCAA program that expects nothing less of excellence. And then watch how YOU change to fit into THEIR culture.

Coaches and Parents

Look at the figure below, this is a theoretical model proposed by Duckworth on how parents (and coaches) should approach their kids/students. Being tough (demanding) but supportive is key. While Duckworth acknowledges that there isn’t any evidence on this as it pertains to grit (she’s working on it), there are plenty of studies on parenting that acknowledge this approach.

To illustrate this point, she provides an example of NFL quarterback Steve Young. Young, who went on to be one of the greatest quarterbacks in NFL history, was initially the 6th string quarterback for BYU. He was so devastated by his lack of playing time that he called his father during the first semester of his freshman year and told him he wanted to drop out and come home. His father’s reply - “you can drop out, but no quitter is going to live with us”. While this may sound harsh, when Duckworth questioned the Young's further, she found that over the years they were exceptionally supportive. And this act wasn’t any different - they knew Steve hadn’t put his best effort forward, and that he needed some ‘tough love’. The rest is history - Steve practiced his throwing (which was his achilles heel early on in college) and by his second year had moved up to 2nd string quarterback. By his junior year he was a starter and in his final year he was one of the best quarterbacks in the country.

Lastly, there’s a concept that Duckworth calls the ‘hard thing rule’. Everyone in her home has to commit to doing something hard, and they can’t back out until the end of the commitment. When reading this, I couldn’t help but think of my old weightlifting coach, and what he had to say about his approach to introducing sport to his children.

His daughter wanted to join gymnastics. For the first month or so, every time he’d drive her to practice, she’d cry and exclaim that it was hard and she didn’t want to go. But it was her decision to join gymnastics. He said that she had to follow through with her commitment. Once the sessions were up, it was her choice whether she wanted to continue or not. What happened after another month went by? While it was still hard, she saw improvement in her abilities, and started to enjoy the challenge. This was over 3 years ago and she’s now one of the best little gymnasts in her age group.

According to Duckworth, when things are tough but we persist nonetheless, often times our perspectives shift. We see growth and learn to enjoy the struggle. Consistency, as we’ve seen, has a large role in building girt.

Final Thoughts

To conclude, I’d like to share a passage from a 2013 article by Duckworth and Eskreis-Winkler that aptly summarizes grit and it’s role in achievement:

“The metaphor of achievement as a race recalls Aesop’s fable of the tortoise and the hare. This oft-told story, which many of us heard as children in one form or another, preaches the value of plodding on, no matter how slow or uneven our progress, toward goals that at times seem impossibly far away. At the starting line, it is the hare who is expected to finish first. Sure enough, the hare quickly outpaces the tortoise, accumulating so great a lead that he lies down to take a nap mid-race. When the hare awakes, the tortoise, who all the while has been laboring toward his destination, is too close to the finish line to beat. Tortoise 1, hare 0.”

In moments when we can’t seem to keep the ball within the lines, when our opponents seem to have more power and strength - let’s remember the story of the hare - and keep pressing on. Surely our fortunes will change.